RECOMS fellow, Zhanna Baimukhamedova is contemplating the life of a faraway-from-home early stage researcher in a time of heightened all-encompassing uncertainty and restrictions to travel.

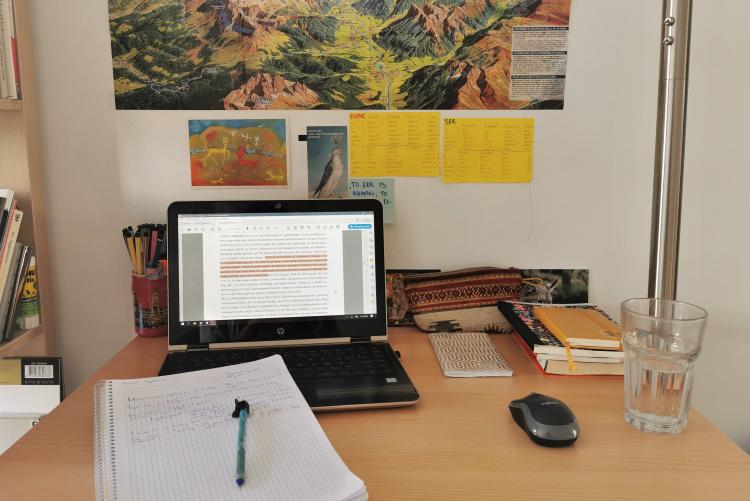

©Zhanna Baimukhamedova

Little things—inviting smell of the morning coffee, a bird’s song, sunlight that briefly caresses my room, tender bud readying to sprout on a nameless plant I picked from the street—all of them make my routine now a little less worrying, a little more wholesome. Stuck inside, I come up with rituals to mark up periods of a surprisingly long day. I am in charge of my schedule—a role that largely used to be taken over by the outside world. Google Maps notifications about traffic in the area make no difference to my life, I start missing the rubbery smell of the metro and the screech of a tram coming to a stop.

To a stop have come lots of things, and, inside, I am waiting for the world to start moving again.

A global pandemic is not something one can prepare for fully. This one has shown that it’s always a good idea to have a stash of toilet paper and, when moving, to pick places that have a balcony or at least a window that does not face a glim concrete wall. Having a pet is a good idea, too, but as a stranger to most places whose current location is always a new name, putting a four-legged companion through all these motions is a rather taxing exercise. Plus, landladies and -lords have a well-known aversion to creatures whom they can’t scare to compliance with the withholding of a deposit. Myself, I’ve compiled an exquisite playlist of cat videos on YouTube that I shuffle through whenever sadness descends.

And sadness is one of many things I go through in lockdown. Having family thousands of kilometers away whom I can't reach quickly in case of an emergency prompts to thinking that maybe I should be there rather than here. Every deviation from the normal functioning of my body makes me think that maybe I've got the virus. I am acutely aware of my every sneeze and cough; every sneeze or cough of others sends me pouncing like a preying jaguar. You see, after two weeks of isolation I have lots of cat analogies.

At the same time, I realize how fortunate I am to have no dependents to take care of at home or faraway kin whose health is faltering when mobility is all but put on a halt. I have a stable income, shelter, and food. We are allowed to leave the house for sports purposes, and I've been taking advantage of that, too. I reach out to many friends whom I have not spoken to for a long time; at once, I started appreciating technology that allows us to see our dear ones from the other side of the globe. Confronted with my thoughts, I continuously contemplate certain aspects of my research, think of its importance, consider what I want to achieve with it, where I want to take it and where I want it to take me.

It’s a weird time in everyone’s lives, and everyone’s a bit scared, concerned, melancholic, down. Things are uncertain and the future is bleak. For many, it will take a long time to re-establish themselves. For some, this pandemic is, sadly, fatal. Being mostly alone at times makes me feel very lonely, isolated, yet at the same time, I am constantly in awe of random acts of solidarity, kindness, and compassion that blossom in the world and in my neighborhood. I wish I could say that I know that everything would end well, but I can't, and no one, it seems, can. When the lockdown is over, when places will start to open up again and people will leave their houses to mingle, things will be different; there will be a new kind of “normal” that we all will have to adapt to.

But for now, it’s the little things—a coffee, a ray of sun, a call from a friend, a new cat video—that make the wait bearable. And we wait.